AIDS/HIV

People have been warned about HIV and AIDS for over twenty years now. AIDS has already killed millions of people, millions more continue to become infected with HIV, and there's no cure – so AIDS will be around for a while yet.

AIDS is one of biggest problems facing the world today and nobody is beyond its reach. Everyone should know the basic facts about AIDS.

What is AIDS?

AIDS is a medical condition. People develop AIDS because HIV has damaged their natural defences against disease.

What is HIV?

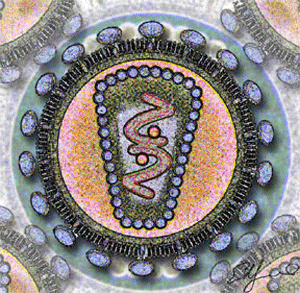

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

HIV is a virus. Viruses infect the cells that make up the human body and replicate (make new copies of themselves) within those cells. A virus can also damage human cells, which is one of the things that can make a person ill.

HIV can be passed from one person to another. Someone can become infected with HIV through contact with the bodily fluids of someone who already has HIV.

HIV stands for the 'Human Immunodeficiency Virus'. Someone who is diagnosed as infected with HIV is said to be 'HIV+' or 'HIV positive'.

Why is HIV dangerous?

The immune system is a group of cells and organs that protect your body by fighting disease. The human immune system usually finds and kills viruses fairly quickly.

So if the body's immune system attacks and kills viruses, what's the problem?

Different viruses attack different parts of the body - some may attack the skin, others the lungs, and so on. The common cold is caused by a virus. What makes HIV so dangerous is that it attacks the immune system itself - the very thing that would normally get rid of a virus. It particularly attacks a special type of immune system cell known as a CD4 lymphocyte.

HIV has a number of tricks that help it to evade the body's defences, including very rapid mutation. This means that once HIV has taken hold, the immune system can never fully get rid of it.

There isn't any way to tell just by looking if someone's been infected by HIV. In fact a person infected with HIV may look and feel perfectly well for many years and may not know that they are infected. But as the person's immune system weakens they become increasingly vulnerable to illnesses, many of which they would previously have fought off easily.

The only reliable way to tell whether someone has HIV is for them to take a blood test, which can detect infection from a few weeks after the virus first entered the body.

When HIV causes AIDS

A damaged immune system is not only more vulnerable to HIV, but also to the attacks of other infections. It won't always have the strength to fight off things that wouldn't have bothered it before.

As time goes by, a person who has been infected with HIV is likely to become ill more and more often until, usually several years after infection, they become ill with one of a number of particularly severe illnesses. It is at this point in the stages of HIV infection that they are said to have AIDS - when they first become seriously ill, or when the number of immune system cells left in their body drops below a particular point. Different countries have slightly different ways of defining the point at which a person is said to have AIDS rather than HIV.

AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) is an extremely serious condition, and at this stage the body has very little defence against any sort of infection.

How long does HIV take to become AIDS?

Without drug treatment, HIV infection usually progresses to AIDS in an average of ten years. This average, though, is based on a person having a reasonable diet. Someone who is malnourished may well progress to AIDS and death more rapidly.

Antiretroviral medication can prolong the time between HIV infection and the onset of AIDS. Modern combination therapy is highly effective and, theoretically, someone with HIV can live for a long time before it becomes AIDS. These medicines, however, are not widely available in many poor countries around the world, and millions of people who cannot access medication continue to die.

How is HIV passed on?

HIV is found in the blood and the sexual fluids of an infected person, and in the breast milk of an infected woman. HIV transmission occurs when a sufficient quantity of these fluids get into someone else's bloodstream. There are various ways a person can become infected with HIV.

Ways in which you can be infected with HIV :

- Unprotected sexual intercourse with an infected person Sexual intercourse without a condom is risky, because the virus, which is present in an infected person's sexual fluids, can pass directly into the body of their partner. This is true for unprotected vaginal and anal sex. Oral sex carries a lower risk, but again HIV transmission can occur here if a condom is not used - for example, if one partner has bleeding gums or an open cut, however small, in their mouth.

- Contact with an infected person's blood If sufficient blood from an infected person enters someone else's body then it can pass on the virus.

- From mother to child HIV can be transmitted from an infected woman to her baby during pregnancy, delivery and breastfeeding. There are special drugs that can greatly reduce the chances of this happening, but they are unavailable in much of the developing world.

- Use of infected blood products Many people in the past have been infected with HIV by the use of blood transfusions and blood products which were contaminated with the virus - in hospitals, for example. In much of the world this is no longer a significant risk, as blood donations are routinely tested.

- Injecting drugs People who use injected drugs are also vulnerable to HIV infection. In many parts of the world, often because it is illegal to possess them, injecting equipment or works are shared. A tiny amount of blood can transmit HIV, and can be injected directly into the bloodstream with the drugs.

It is not possible to become infected with HIV through :

- sharing crockery and cutlery

- insect / animal bites

- touching, hugging or shaking hands

- eating food prepared by someone with HIV

- toilet seats

HIV facts and myths

People with HIV look just like

everybody else

Around the world, there are a number of different myths about HIV and AIDS. Here are some of the more common ones :

'You would have to drink a bucket of infected saliva to become infected yourself' . . . Yuck! This is a typical myth. HIV is found in saliva, but in quantities too small to infect someone. If you drink a bucket of saliva from an HIV positive person, you won't become infected. There has been only one recorded case of HIV transmission via kissing, out of all the many millions of kisses. In this case, both partners had extremely badly bleeding gums.

'Sex with a virgin can cure HIV' . . . This myth is common in some parts of Africa, and it is totally untrue. The myth has resulted in many rapes of young girls and children by HIV+ men, who often infect their victims. Rape won't cure anything and is a serious crime all around the world.

'It only happens to gay men / black people / young people, etc' . . . This myth is false. Most people who become infected with HIV didn't think it would happen to them, and were wrong.

'HIV can pass through latex' . . . Some people have been spreading rumours that the virus is so small that it can pass through 'holes' in latex used to make condoms. This is untrue. The fact is that latex blocks HIV, as well as sperm - preventing pregnancy, too.

What does 'safe sex' mean?

Safe sex refers to sexual activities which do not involve any blood or sexual fluid from one person getting into another person's body. If two people are having safe sex then, even if one person is infected, there is no possibility of the other person becoming infected. Examples of safe sex are cuddling, mutual masturbation, 'dry' (or 'clothed') sex . . .

In many parts of the world, particularly the USA, people are taught that the best form of safe sex is no sex - also called 'sexual abstinence'. Abstinence isn't a form of sex at all - it involves avoiding all sexual activity. Usually, young people are taught that they should abstain sexually until they marry, and then remain faithful to their partner. This is a good way for someone to avoid HIV infection, as long as their husband or wife is also completely faithful and doesn't infect them.

What is 'safer sex'?

Safer sex is used to refer to a range of sexual activities that hold little risk of HIV infection.

Safer sex is often taken to mean using a condom for sexual intercourse. Using a condom makes it very hard for the virus to pass between people when they are having sexual intercourse. A condom, when used properly, acts as a physical barrier that prevents infected fluid getting into the other person's body.

Is kissing risky?

Kissing someone on the cheek, also known as social kissing, does not pose any risk of HIV transmission.

Deep or open-mouthed kissing is considered a very low risk activity for transmission of HIV. This is because HIV is present in saliva but only in very minute quantities, insufficient to lead to HIV infection alone.

There has only been one documented instance of HIV infection as a result of kissing out of all the millions of cases recorded. This was as a result of infected blood getting into the mouth of the other person during open-mouthed kissing, and in this instance both partners had seriously bleeding gums.

Can anything 'create' HIV?

No. Unprotected sex, for example, is only risky if one partner is infected with the virus. If your partner is not carrying HIV, then no type of sex or sexual activity between you is going to cause you to become infected - you can't 'create' HIV by having unprotected anal sex, for example.

You also can't become infected through masturbation. In fact nothing you do on your own is going to give you HIV - it can only be transmitted from another person who already has the virus.

Is there a cure for AIDS?

HIV medication can slow the progress of the virus

Worryingly, surveys show that many people think that there's a 'cure' for AIDS - which makes them feel safer, and perhaps take risks that they otherwise shouldn't. These people are wrong, though - there is still no cure for AIDS.

There is antiretroviral medication which slows the progression from HIV to AIDS, and which can keep some people healthy for many years. In some cases, the antiretroviral medication seems to stop working after a number of years, but in other cases people can recover from AIDS and live with HIV for a very long time. But they have to take powerful medication every day of their lives, sometimes with very unpleasant side effects.

There is still no way to cure AIDS, and at the moment the only way to remain safe is not to become infected.

There is no cure for AIDS. Although antiretroviral treatment can suppress HIV – the virus that causes AIDS – and can delay illness for many years, it cannot clear the virus completely. There is no confirmed case of a person getting rid of HIV infection. Sadly, this doesn’t stop countless quacks and con artists touting unproven, often dangerous “AIDS cures” to desperate people.

It is easy to see why an HIV positive person might want to believe in an AIDS cure. Access to antiretroviral treatment is scarce in much of the world. When someone has a life-threatening illness they may clutch at anything to stay alive. And even when antiretroviral treatment is available, it is far from an easy solution. Drugs must be taken every day for the rest of a person’s life, often causing unpleasant side effects. A one-off cure to eradicate the virus once and for all is much more appealing.

Distrust of Western medicine is not uncommon, especially in developing countries. The Internet abounds with rumours of the pharmaceutical industry or the U.S. government suppressing AIDS cures to protect the market for patented drugs. Many people would prefer a remedy that is “natural” or “traditional”.

Where’s the harm in fake AIDS cures?

Unproven AIDS cures have been around since the syndrome emerged in the early 1980s. In most cases, they have only served to worsen suffering.

First of all, fake cures are a swindle. Someone who invests their savings in a worthless potion or an electrical zapper has less money to spend on real medicines and healthy food.

Many peddlers of bogus cures insist their clients avoid all other treatments, including antiretroviral medicines. By the time a patient realises the “cure” hasn’t worked, their prospects for successful antiretroviral treatment may well have diminished.

Fake cures may also cause direct harm to health. Inventors often refuse to reveal their recipes. Some so-called cures have been found to contain industrial solvents, disinfectants and other poisons. The dangers posed by the virgin cleansing myth – which advocates sex with children as a cure for AIDS – are only too clear.

Finally, the promotion of fake AIDS cures undermines HIV prevention. People who believe in a cure are less likely to fear becoming infected with HIV, and hence less likely to take precautions.

Why is it so difficult to cure AIDS?

Curing AIDS is generally taken to mean clearing the body of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. The virus replicates (makes new copies of itself) by inserting its genetic code into human cells, particularly a type known as CD4 cells. Usually the infected cells produce numerous HIV particles and die soon afterwards. Antiretroviral drugs interfere with this replication process, which is why the drugs are so effective at reducing the amount of HIV in a person’s body to extremely low levels. During treatment, the concentration of HIV in the blood often falls so low that it cannot be detected by the standard test, known as a viral load test.

Unfortunately, not all infected cells behave the same way. Probably the most important problem is posed by “resting” CD4 cells. Once infected with HIV, these cells, instead of producing new copies of the virus, lie dormant for many years or even decades. Current therapies cannot remove HIV’s genetic material from these cells. Even if someone takes antiretroviral drugs for many years they will still have some HIV hiding in various parts of their body. Studies have found that if treatment is removed then HIV can re-establish itself by leaking out of these “viral reservoirs”.

A cure for AIDS must somehow remove every single one of the infected cells.

Reputable research on curing AIDS

A wide range of strategies – including such drastic measures as bone marrow transplantation – have failed in trials to eradicate HIV infection. Currently many researchers believe the best approach is to combine antiretroviral treatment with drugs that flush HIV from its hiding places. The idea is to force resting CD4 cells to become active, whereupon they will start producing new HIV particles. The activated cells should soon die or be destroyed by the immune system, and the antiretroviral medication should mop up the released HIV.

Early attempts to employ this technique used interleukin-2 (also known as IL-2 or by the brand name Proleukin). This chemical messenger tells the body to create more CD4 cells and to activate resting cells. Researchers who gave interleukin-2 together with antiretroviral treatment discovered they could no longer find any infected resting CD4 cells. But interleukin-2 failed to clear all of the HIV; as soon as the patients stopped taking antiretroviral drugs the virus came back again.1 2

There is a problem with creating a massive number of active CD4 cells: despite the antiretroviral drugs, HIV may manage to infect a few of these cells and replicate, thus keeping the infection alive. Scientists are now investigating chemicals that don’t activate all resting CD4 cells, but only the tiny minority that are infected with HIV.

One such chemical is valproic acid, a drug already used to treat epilepsy and other conditions. In 2005 a group of researchers led by David Margolis caused a sensation when they reported that valproic acid, combined with antiretroviral treatment, had greatly reduced the number of infected resting CD4 cells in four patients. They concluded that:

“This finding, though not definitive, suggests that new approaches will allow the cure of HIV in the future.”3

Sadly, it seems such optimism was premature; more recent studies suggest that valproic acid cannot eradicate HIV.4 In fact it’s quite possible that all related approaches are flawed because the virus has other hiding places besides resting CD4 cells. There is a lot about HIV that remains unknown.

Some of the world’s top research institutions are today engaged in studies to learn more about the behaviour of HIV, resting CD4 cells and other hiding places. But the truth is that this field does not receive a lot of funding. Some people think the search for a cure is not worth much investment because the task may well be impossible.

Yet there are still those who remain hopeful, including the research charity amfAR, which in 2006 awarded nearly $1.5 million to AIDS cure researchers. Activist Martin Delaney is among those calling for an end to defeatism:

“Far too many people with HIV, as well as their doctors, have accepted the notion that a cure is not likely. No one can be certain that a cure will be found. No one can predict the future. But one thing is certain: if we allow pessimism about a cure to dominate our thinking, we surely won’t get one… We must restore our belief in a cure and make it one of the central demands of our activism.”5

How to spot fake AIDS cures and treatments

As already stated, there is no proven cure for AIDS. The best advice is to steer clear of anyone claiming otherwise. For those who find themselves tempted, here are a few pointers for spotting quack therapies.

Who makes the claims?

Try to find some information about the person or people promoting the product. What are their credentials? If someone claims to be a doctor then they should say what type of doctor, and where they got their qualifications.

What claims do they make?

Look at how the product is presented. Reputable scientists and doctors don’t use sensational terms such as “miracle breakthrough”. Also watch for evidence of poor scientific understanding; for example, no expert would refer to HIV as “the HIV virus” or “the AIDS virus”.

It is very rare for a medicine to be 100% effective for all patients. It is highly implausible that a single product could cure a wide range of unrelated diseases such as cancer, asthma, AIDS and diabetes. A real scientist would be extremely wary of making such claims.

What’s in the cure?

Many inventors won’t reveal what goes into their so-called cures. Ask yourself why this might be. Could it be that their methods wouldn’t stand up to scientific scrutiny?

It is important to remember that words like “natural” and “herbal” are no guarantee of safety. After all, hemlock and ricin (derived from castor beans) are both entirely natural and extremely toxic. As the U.S. Food and Drug Administration points out,

“Any product – synthetic or natural – potent enough to work like a drug is going to be potent enough to cause side effects.”6

What evidence do they offer?

To gain the approval of medical authorities, any new treatment must undergo very extensive testing. Countless products destroy HIV in the laboratory but are ineffective or dangerous when used by people. A proper trial involves a large group of volunteers divided randomly into two sets. One half uses the test product and the other receives a placebo (a harmless pretend medicine that looks like the real thing). During the trial, neither the scientists nor the volunteers should know who is getting which treatment. Afterwards, the results for the two groups are compared to see if the test product performed better than the placebo.

Virtually all promoters of “AIDS cures” cannot provide any data from large-scale, randomised human trials. Instead they rely on anecdotes, personal testimonies, laboratory experiments or small-scale trials with no placebo comparison. This type of evidence is always unreliable.

Personal testimonies are notoriously untrustworthy. Usually there is no way of knowing whether the people in question ever existed, let alone whether they were helped by the therapy. There have been cases of people being paid to pretend they’ve been cured. And even if a handful of people really did get better after they took the treatment, this doesn’t necessarily mean that it works; the improvements may just have been a coincidence. Many negative reports may have been left out of the promotional material.

Proving that HIV has been eradicated isn’t easy. Changes in symptoms or weight gain are not sufficient, and neither is a viral load test. Even if the test can’t detect HIV in the bloodstream (perhaps because the person has been on antiretroviral therapy), this doesn’t mean the virus has been cleared from all parts of the body. Much more thorough investigation is needed.

Beware of conspiracy theorists

Many sellers of fake medicines fall back on conspiracy theories to explain why their products haven’t undergone proper testing. They say that government agencies and the medical profession seek to suppress alternative treatments to safeguard the profits of the pharmaceutical industry.

This kind of allegation is a sure sign of a charlatan. In reality, leading scientists investigate all kinds of therapies that can’t be patented. For example, the U.S. government has funded research into using generic drugs (such as valproic acid) and human hormones (such as interleukin-2) as aids to ridding the body of HIV infection.

Do some research

Any important medical breakthrough will be reported in peer-reviewed journals such as Nature, Science or The Lancet. The mainstream media will pick up the story and leading experts will express their opinions.

Simply typing the name of a supposed cure into an Internet search engine and reading some of the resulting web pages will quickly establish whether it has widespread support. It is also worth searching an online medical database such as PubMed for scientific studies and reviews.

Consult an expert

Always talk to a doctor or other health professional before trying any medical treatment. If you need more information or a second opinion, try contacting a reputable health organisation or telephone helpline. Several American states have AIDS Fraud Task Forces dedicated to combating quackery, and local Food and Drug Administration offices can provide details of any action taken against a product or its manufacturer. Similar agencies operate in most other parts of the world.

President Jammeh’s AIDS cure

President Jammeh of The Gambia, a small country in West Africa, made a dramatic announcement in January 2007:

“I can treat asthma and HIV/AIDS and the cure is a day’s treatment. Within three days the person should be tested again and I can tell you that he/she will be negative... The mandate I have is that HIV/AIDS cases can be treated on Thursdays. That is the good news and the bad news is that I cannot treat more than ten patients every Thursday.”7

Three weeks later the president’s office released the results of viral load tests conducted on the first batch of patients. According to the official statement, “the herbal medicine and therapy administered by President Jammeh have yielded results beyond all reasonable doubts, that they are effective and can cure AIDS.”8 On closer inspection, however, the findings were far from convincing.

Of the four patients with HIV-1, one had a very high viral load, one high, one moderate, and one undetectable. Of the four patients with HIV-2, one had a low viral load and three had less than the detectable level.9

The fact that half of the patients still had detectable virus in their blood shows that the president’s cure cannot be 100% effective. More importantly, as already noted, an undetectable viral load does not prove that HIV has been eradicated. Some of the patients had previously been taking antiretroviral therapy, which often renders the virus undetectable. Apparently no evaluation was done before the president’s treatment began.

The viral load tests were conducted at a university in Dakar, Senegal, using samples of the patients’ blood. It has since emerged that the scientists who ran the tests were not aware of the samples’ origin. The Senegalese experts rebutted the president’s interpretation of their findings:

“There is no baseline ... you can’t prove that someone has been cured of AIDS from just one data point. It’s dishonest of the Gambian government to use our results in this way” - Dr. Coumba Toure Kane10

“The interpretation by the Gambian authorities of the results of HIV antibody and viral load testing on blood samples sent to my laboratory is incorrect... Of those samples that were HIV-positive (66.66%), none could be described as cured.” - Professor Souleymane Mboup11

The results of a second set of viral load tests, conducted by the National Institute of Hygiene in Morocco, were released in March 2007. For the first set of patients the numbers were similar to those found in Senegal. Among 31 other patients only six had undetectable viral loads.12

Clinical data for the third and fourth batch were released in October 2007. On this occasion the State House chose to withhold the name of the country in which the samples were tested. Twenty-seven of the seventy patients were found to have undetectable viral loads. Another twenty-seven had viral load counts above half a million, which is considered to be very high. The CD4 counts for twenty-seven of the seventy patients were below 200, which means they had progressed from HIV infection to AIDS. Curious repetitions within the viral load count data cast doubt on their accuracy.13

At least two of the president’s patients are known to have died.14

These unpromising outcomes have not shaken the president’s belief in his treatment, which is endorsed by the Gambian health ministry and is administered at state hospitals. President Jammeh, who has no medical qualifications, refuses to disclose exactly what goes into his cure. All he has revealed is that it involves seven herbs, “three of which are not from Gambia.”15 The treatment involves a green paste and a grey liquid each applied to the patient’s skin, and a yellowish tea-like drink. Even more important, according to President Jammeh, is the power of prayer:

“For everything that we do 90% we have to invoke the name of almighty Allah, and then 10% is what the herbs take care of.”16

Leading AIDS experts have expressed serious concern about President Jammeh’s exploits. According to Dr. Pedro Cahn, President of the International AIDS Society:

“It is premature and unethical to label this product a cure if it has not been thoroughly tested and proven. Furthermore, to take patients off potent combination antiretroviral therapy, which has saved millions of lives since its introduction in 1996, is shocking and irresponsible.”17

A fifth batch of 150 patients began treatment in February 2008.18

Other herbal cures

Herbal mixtures comprise the most popular form of alternative AIDS therapy. Although it is possible that some of these treatments may benefit people with HIV, none is a proven cure.

- Comforter’s Healing Gift, a South African company, produces an extract of a plant called sonneblom (not sunflower). According to Freddie Isaacs, the inventor of the treatment and a co-director of the company, this product is a cure for AIDS.19 Other spokespersons have said such claims go against company policy, and the product should be described as a nutritional supplement until it has undergone proper testing. According to some reports one of South Africa’s leading attorneys, Christine Qunta, is closely connected with Comforter’s Healing Gift. South Africa’s opposition party has laid a charge against Qunta of authorising the sale of an unlicensed medicine.20

- Dr. Sebi (born Alfredo Bowman) says his “electric foods” can cure AIDS, cancer and many other illnesses. Sebi, who has offices in Honduras and the USA, has no medical qualifications and many of his views are totally at odds with basic principles of mainstream science. In Sebi’s opinion, AIDS (like all other diseases) occurs when “the mucous membrane has been compromised”.21 He says his plant extracts cure the illness by removing the mucous. Sebi was arrested in 1987 and again in 1997 for publishing false health claims and practising medicine without a licence.22 23 He has published no verifiable evidence to support his “AIDS cure”.

- IMOD was developed by scientists from Russia and Iran. When the Iranian government unveiled the drug in February 2007, many media sources, including Iran’s Fars News Agency, described IMOD as an “AIDS cure”.24 The official IMOD website makes no such claim, but does say that human trials of the drug found it increased CD4 counts in HIV positive people.25 No study reports have been published in medical journals. The research team did not respond to emails from the author of this article.

- Khomeini (or Khomein) was invented by Professor Sheik Allagholi Elahi of Iran, who set up a clinic in Uganda to sell this so-called AIDS cure for more than $1,500 per patient. The Ugandan Ministry of Health appointed a team of experts to monitor some of the few hundred people taking the treatment. After their study showed Elahi’s claims to be false, the government banned the use and distribution of Khomeini in April 2006, and Ehahi was arrested.26

- MAB Formula One and MAB Formula Two were developed by Ghanaian doctors and ethno-botanists led by Dr. Jacob Akumoah-Boateng. According to the researchers MAB Formula One kills HIV while MAB Formula Two boosts the immune system. Dr. Akumoah-Boateng says tests in the U.S. demonstrated the disappearance of HIV and HIV antibodies after the treatment was given, though none of the findings have been published in the medical literature.27

Ubhejane, a brown liquid said to be made from 89 herbs, has been taken by many hundreds of HIV positive South Africans. Its creator, Zeblon Gwala, says Ubhejane reduces viral load and increases CD4 counts in HIV positive people. He advises that it should not be taken at the same time as antiretroviral treatment.

Ubhejane has often been referred to as a “cure for AIDS” and Gwala’s employees have reportedly promoted it as such, despite having no evidence from rigorous human trials.28 29 Scientists who have tested Ubhejane in the laboratory have stressed that they haven’t demonstrated any benefits to patients.30 South Africa’s opposition party has attempted to have Gwala prosecuted for fraud.31 In 2008, the Advertising Standards Authority of South Africa demanded the withdrawal of an advertisement stating that Ubhejane boosted immunity and reduced viral load, having found these claims to be unsubstantiated.32

Chemicals

Many people mistakenly believe that what destroys HIV in the test tube must also work in the human body. This is one reason why a number of disinfectants and other chemicals have been wrongly promoted as cures for AIDS.

- Armenicum (also known as iodine-lithium-alpha-dextrin or ILalphaD) is a type of iodophor, a chemical that slowly releases iodine when mixed with water. According to Armenian scientists Armenicum, injected into the bloodstream, acts as an antiretroviral drug by blocking the replication of HIV. They claim to have evidence that the substance reduces viral load and increases CD4 counts in HIV positive people. The inventor of Armenicum, Alexander Ilyen, once said he was convinced it would lead to an AIDS cure.33 No studies of HIV positive people treated with Armenicum have been published in peer-reviewed journals. In a report on an animal experiment published in June 2007 the Armenicum research team admits that, “The systemic therapeutic application of iodophores has not yet been accepted”.34 A BBC investigation of Armenicum in 1999 found that the health of two American men got worse after they took the drug.35

- Colloidal silver is a suspension of extremely tiny silver particles in water. Many websites say this clear, colourless liquid effectively treats a wide range of bacterial and viral infections, including HIV infection. While it is true that colloidal silver kills germs in laboratory conditions, there is no reliable evidence of any benefit in people. Contrary to the claims of many retailers, colloidal silver is not harmless. Regular use can cause an irreversible bluish-grey discolouration of the skin, known as argyria.36 Consuming very large amounts of colloidal silver may lead to neurologic problems, kidney damage, stomach distress, headaches, fatigue, and skin irritation.37 There has been at least one reported case of a man falling into a coma after ingesting colloidal silver.38 In America it is illegal for retailers to make any health claims for this product.39

- Tetrasil (or Imusil) is a substance containing tetrasilver tetroxide. A patent held by Dr. Marvin S. Antelman claims that this simple chemical compound cures AIDS by “electrocuting” HIV.40 Dr. Antelman admits his approach to AIDS is “non-conventional” and he does not trust viral load tests: “Accordingly we have patients who display viral load reduction and those that do not who are nevertheless cured of AIDS”, he has said.41 Tetrasilver tetroxide is more commonly used for disinfecting swimming pools.42 After it was promoted as an AIDS cure in Zambia the government banned Tetrasil because it has no proven benefits for people living with HIV.43 In America it is illegal to promote Tetrasil for the treatment or prevention of any disease.44

- Virodene is based on the industrial solvent dimethylformamide (DMF). In the late 1990s this chemical was touted as a possible cure for AIDS. For several years senior members of the South African government, including Thabo Mbeki, vehemently supported research into Virodene as an AIDS treatment, against the advice of medical experts. South Africa’s drug regulators have long prohibited use of Virodene as it has no proven benefits. Laboratory studies have found that DMF does not destroy HIV or inhibit its replication. The only trial of its effectiveness in humans, conducted in Tanzania, found that Virodene did not reduce viral load and had only marginal effects on the immune system.45 DMF is considered a toxic substance; workers are advised to avoid skin contact with the chemical because it may cause serious liver damage.46 47 Imunoxx, which a Namibian company markets as an immune booster, is essentially identical to Virodene.

Oxygen therapy

- Hydrogen peroxide, diluted in water, is commonly used as a bleach and a disinfectant. Some alternative health practitioners advocate drinking, injecting or bathing in weak solutions of this chemical as a cure for AIDS, flu, cancer and other illnesses. There is no evidence to support these claims. Several people have died as a result of swallowing or injecting hydrogen peroxide.48 49

- Ozone is an unstable form of oxygen gas. Ozone therapy has been proposed as a treatment or cure for many illnesses, including HIV infection. One delivery method is autohemotherapy, which involves removing some of a patient’s blood, exposing it to ozone, and then putting it back into the patient. Alternatives include pumping the gas into the rectum, drinking water containing ozone bubbles (ozonized water, which contains hydrogen peroxide), or injecting the gas into the bloodstream. Studies of ozone autohemotherapy in HIV positive people have found it has no significant effect on CD4 counts and other outcomes.50 51 According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “Ozone is a toxic gas with no known useful medical application in specific, adjunctive, or preventive therapy. In order for ozone to be effective as a germicide, it must be present in a concentration far greater than that which can be safely tolerated by man and animals.”52 It is illegal for retailers in America to make any health claims for ozone generators.

Electrical zappers

- Dr. Hulda Clark (who is not a licensed medical doctor) promotes a range of products said to cure AIDS including an electrical “zapper” which, by generating low voltage electricity, is supposed to kill parasites, bacteria and viruses in the body. No proper studies of the zapper have been conducted. Dr. Clark’s methods of diagnosing HIV are highly unconventional; she believes that HIV comes from intestinal worms in the presence of benzene, and that HIV can be found in snails.53 It is therefore doubtful whether the people she claims to have cured of HIV infection were ever really infected.54 Dr. Clark left America after being taken to court for practising medicine without a licence.55 She now runs a clinic in Tijuana, Mexico, where she has also run into trouble with the authorities.56

- The Bob Beck Protocol involves a set of therapies devised by the late Dr. Bob Beck (who was not a medical doctor) that are supposed to cure AIDS, cancer and all other diseases. The four components are electric currents, magnetic pulses, colloidal silver and ozonized water. There is no good evidence that electricity can cure any infection. Claims about the healing powers of Bob Beck’s devices are based entirely on test tube studies and unverifiable anecdotes.

Immune boosters

Some so-called AIDS cures are meant to stimulate the human immune system. Since HIV makes new copies of itself by infecting active immune cells, there is a real danger that such therapies will hasten the spread of the virus rather than contain it.

- Dr. Gary R. Davis got his idea for an AIDS cure from a goat that appeared in his dreams. The late Dr. Davis never prescribed his goat serum treatment (known as BB7075) to HIV positive Americans due to legal restrictions. In 1998 one young girl, Precious Thomas, was given the serum by her mother, who stole it from Davis’ office. Some websites say the girl was cured of HIV infection, based on a viral load test conducted soon afterwards.57 In a 2006 interview, however, Precious Thomas makes clear that she is still infected with HIV.58 After being denied approval in America, Dr. Davis and his associates tried to conduct goat serum trials in Ghana. Again he was stopped because “the supporting evidence for asking for registration and use of the serum was totally inadequate”.59 In late 2006, a few months before Dr. Davis’ death, the BBC exposed an attempt by a British company to test the substance on dozens of people in Swaziland, despite the lack of toxicity tests and other necessary preliminary studies.60

- The Antidote – a drug derived from a crocodile protein – has been promoted via spam email and websites with the promise that “It kills all known deadly viruses and bacteria in the body”.61 Absolutely no scientific evidence has been offered to support this claim.

- V-1 Immunitor (or V-AIM or Immureboost) is a pink pill containing antigens taken from the pooled blood of HIV positive people. A clinic in Thailand began distributing V-1 in 2001. Demand soared when the pill’s inventor, Vichai Jirathitikal, said it had eliminated HIV in two patients.62 The Thai Ministry of Public Health responded by conducting a study of those receiving V-1; the findings were not encouraging. According to a government minister, “the pill does not have any effect on the body’s immune system, white blood cell count and amount of the virus in the blood”.63 Other studies of the so-called vaccine – all carried out by employees of its manufacturer – do not provide convincing evidence of benefit. AIDS patients treated with V-1 typically survive for a matter of weeks, as opposed to the years achieved through antiretroviral treatment.64 Although the company has said that people treated with V-1 have “serodeconverted” from HIV-positive to HIV-negative,65 this claim is based on unreliable evidence and is not taken seriously by the scientific community.66 The manufacturing and sales licences for V-1 in Thailand were revoked in April 2003.67 68 Apparently undaunted, Vichai Jirathitikal and a company called Immureboost have continued to promote the product under the new name V-AIM, describing it as a therapeutic vaccine rather than a cure for AIDS.69

Faith-based cures

Religious bodies have done much to help the response to AIDS, especially by caring for the sick. Sadly a small minority of religious leaders have abused the trust placed in them by promising to cure AIDS through faith, sometimes in exchange for money or gifts. Most reports come from sub-Saharan Africa, where evangelical Americans are among those implicated.70

One of the most startling examples of recent times concerns an Ethiopian church where thousands of HIV positive people have sought a cure in showers of holy water. At one time, pilgrims were told to trust in faith alone and to refuse medication.71 Church patriarch Abune Paulos has since endorsed the use of antiretroviral treatment:

“What we are saying is taking the drugs is neither a sin nor a crime. Both the Holy Water and the medicine are gifts of God. They neither contradict nor resist each other.”72

The virgin cleansing myth

The myth that sex with a virgin can cure sexually transmitted diseases has a long history in Europe and elsewhere. Since the emergence of the AIDS epidemic, there has been much concern that this belief might encourage the rape of children, especially in Africa where HIV is widespread. A number of horrific reports in the popular press have fuelled such anxiety.

Belief in the virgin cleansing myth has been reported from Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. There is no doubt that it has led to abuse of not only children but also the disabled (who are often assumed to be virgins).73 Nevertheless, the scale of the myth’s impact is disputed because it is not the only motivation behind child rape.74 75 In many cases the goal is more likely to be prevention than cure: men are seeking partners who are less likely to have HIV.

Thankfully efforts are being made to dispel the virgin cleansing myth around the world. But to effectively clamp down on child rape, such campaigns must be accompanied by changes to the cultural and legal environment that enables abuse to take place.

Spontaneous cures: Andrew Stimpson

Occasionally there are reports of HIV seeming to vanish for no obvious reason. One especially sensational story broke on 13th November 2005, when two British newspapers reported that a 25-year old Scot, Andrew Stimpson, had become the first person to be cured of HIV infection.76 77

In interviews with the two papers, Stimpson said he first suspected he might have HIV in 2002, after several weeks of feeling tired and feverish. Knowing his partner had been HIV positive for a number of years, Stimpson visited the Victoria Sexual Health Clinic in London for an HIV antibody test in May. The result was negative, but he was encouraged to return for further tests, as HIV antibodies often do not appear in the blood until several weeks or even months after initial infection.

In August 2002, Stimpson returned for three more HIV antibody tests. His first, taken on the 15th, was “indeterminate” (i.e. neither definitely positive nor negative), but the following two (taken on 20th and 23rd August) both found him to be HIV antibody positive. However, a viral load test showed the amount of virus in his blood was low, so he was not prescribed antiretroviral therapy. He made a personal choice to start taking multivitamin and mineral tablets and other dietary supplements.

For fourteen months Stimpson remained surprisingly healthy, so much so that, in October 2003, his doctor offered him a repeat test for HIV antibodies. Remarkably, the test came back negative. Two more, carried out in December 2003 and March 2004, also gave negative results.

Andrew Stimpson tried to launch a legal case against the Chelsea and Westminster NHS Trust (CWT) which had tested him, assuming his results had been mixed up with those of another client. The blood samples associated with his original positive diagnosis and his subsequent negative results were retested, and the DNA from the samples compared to his. All the samples were found to belong to Stimpson, and retesting produced the same “positive then negative” antibody results. According to Stimpson:

“After the repeat tests my doctor came into the room saying, ‘You’ve cured yourself! This is unbelievable.’”78

Andrew Stimpson’s story became an overnight media sensation. But a statement from the CWT cast doubt on the cure claims:

“It is probable that there was never any evidence of Mr Stimpson having the HIV virus but rather that there was transient evidence of an antibody response to the virus present in his bloodstream when he had the initial tests... The antibody testing is exquisitely sensitive and the smallest measure can be recorded which is probably what happened in this case.”79

A spokesperson for the CWT later said they had not categorically stated that Andrew Stimpson’s case was an example of a false positive test result, but that it was one of a number of scenarios that needed to be considered.80 The media quickly accepted the “false positive” explanation, and by the end of the month the story had ceased to be of interest to them.

The only news since then dates from June 2006, when the Guardian newspaper reported that Stimpson was still working with doctors, but that because of medical confidentiality, very little more was known about the case. However, Anna Maria Geretti, a clinical virologist at the Royal Free Hospital, was willing to speculate:

“These follow-up tests are very complicated. They could take over six months. But personally, I’m sceptical that they will find a cure from this case.”81

The most likely explanation remains the occurrence of a highly unusual false positive antibody test result. This may happen if the test detects a non-HIV antibody (i.e. a similar antibody produced against a different virus) or, theoretically, because there are somehow HIV antibodies present without an actual HIV infection. Occasionally a false positive may be the result of a faulty test, though a second backup test would normally eliminate this possibility.

Although receiving three false positive results would be exceedingly unusual, some scientists believe it is more plausible than a spontaneous cure. In any case it’s extremely unlikely that, as some newspapers suggested, the multivitamins and dietary supplements that Andrew Stimpson took would have had any effect on his “seroreversion” (the process of going from HIV antibody positive to HIV antibody negative). Millions of people living with HIV take multivitamins and minerals; while such supplements may help to maintain good general health, there is no evidence that they can eliminate HIV infection.

World Impact

To understand the devastation of AIDS, you have to understand the high mortality rate of people who develop the disease. If you counted every person in the city of Chicago, which is about 3 million, you would get the idea of how many people died worldwide from AIDS in 2000. Basically, that means that each year AIDS kills the same number of people that populate the third largest city in the United States.

More then 36 million people are infected with the HIV virus worldwide, with 25.3 million of those cases in sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, anther 5.3 million new HIV infections occurred in 2000, which represents about 16,000 new cases per day. The regions with the greatest number of people living HIV/AIDS, according to the World Health Organization, include:

- Sub-Saharan Africa - 25.3 million

- South and Southeast Asia - 5.8 million

- Latin America - 1.4 million

- North America - 920,000

- Eastern Europe/Central Asia - 700,000

In the United States, 753,907 cases had been reported to the CDC through June 2000. However, the CDC estimates that as many as 900,000 Americans are living with HIV or AIDS.

..

HIV/AIDS History

- 1926-46 - HIV possibly spreads from monkeys to humans. No one knows for sure.

- 1959 - A man dies in Congo in what many researchers say is the first proven AIDS death.

- 1981 - The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notices high rate of otherwise rare cancer

- 1982 - The term AIDS is used for the first time, and CDC defines it.

- 1983/84 - American and French scientists each claim discovery of the virus that will later be called HIV.

- 1985 - The FDA approves the first HIV antibody test for blood supplies.

- 1987 - AZT is the first anti-HIV drug approved by the FDA.

- 1991 - Basketball star Magic Johnson announces that he is HIV-positive.

- 1996 - FDA approves first protease inhibitors.

- 1999 - An estimated 650,000 to 900,000 Americans living with HIV/AIDS.

- 2001 - AIDS global death toll reaches nearly 22 million.